- Contact

- Book

- 3D Foundation

- Butler Elite

- Staff

- 2018 17U

- - 2018 17U Photos

- - 2018 17U Videos

- 2019 16U

- - 2019 16U Photos

- - 2019 16U Videos

- 2020 15U

- - 2020 15U Photos

- - 2020 15U Videos

- 2021 14U

- - 2021 14U Photos

- - 2021 14U Videos

- 2022 13U

- - 2022 13U PHOTOS

- - 2022 13U VIDEOS

- 2023 12U

- - 2023 12U PHOTOS

- - 2023 12U VIDEOS

- 2024 11U

- - 2024 11U Photos

- - 2024 11U Videos

- 2025 10U

- - 2025 10U Photos

- - 2025 10U Videos

- Information

- Media

- Bio

The Great Escape

RACINE, Wis. The 17-year-old was home sick from school, napping away the effects of the flu, when he awoke to sirens and the chatter of a crowd gathering at the A&W restaurant across the street. Rolling over in bed, he peered through the blinds to see flashing lights and armed police officers, dressed in black, approaching.

He had served nine months in jail because of a drug and weapons conviction, but that had occurred more than a year before. He had been clean since. What could this be about? Panicked, he did the only thing that came to mind: He pulled the covers over his head and pretended to be asleep.

After the police broke down the front door and found him, they handcuffed him, struggling to get a cuff around the right hand he had broken playing basketball a few weeks earlier. They took him downstairs and planted him on a living room couch. Wearing a tank top, boxer shorts and a perturbed expression, he watched investigator Richard Geller and his officers scour the two-story yellow bungalow. Eventually, Geller found 15 grams of crack cocaine -- worth about $1,500 in Racine in 1998 -- hidden in the garage.

"Bingo!" Geller shouted. "Jackpot! We got it!"

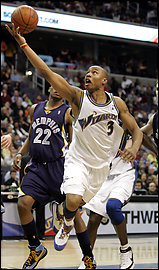

It was at that moment that Caron Butler's life could have careened to a far different place: away from a successful college basketball career at Connecticut; away from the Washington Wizards and the five-year, $50 million contract he signed while crying in 2005; and away from being named to today's NBA All-Star Game for the second consecutive year.

But Butler wasn't sent back to jail on what he called "one of the scariest days of my life." Instead, he was freed to continue his remarkable journey from youth prison in Wisconsin to Verizon Center because a police officer made a decision that changed a life.

"The graveyards and prisons are full of people that wanted a second chance," Butler said. "God put his hands on my life. He said 'I'm going to touch you so that you can touch others.' "

Trouble From the Start

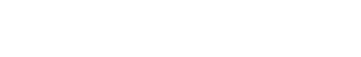

The rise of Butler, 27, from small-time drug dealer to NBA star began here, in this waterfront city of 80,000 just south of Milwaukee. "A lot of people judge your glory without knowing your story," Butler said one afternoon last fall, as he strolled around the neighborhood that created the man Wizards Coach Eddie Jordan calls "Tuff Juice."

He grew up on Racine's south side, a neighborhood of decaying homes and dilapidated buildings, and played pickup basketball at a nearby community center. Aside from visitors to Wells Brothers pizza, this area doesn't draw many outsiders. It's sprinkled with a few corner convenience stores. Butler's favorite spot, a Mexican dive called La Tapatia, has just one table. A little store is attached, where you can buy a bottle of Pepto-Bismol with your burrito.

Racine is so small that Butler's neighborhood is less than six blocks from million-dollar, waterfront estates on Lake Michigan. But the peaceful waters couldn't match the lure of Hamilton Park, a patch of grass on 18th Street between Howe and Mead with a sparse playground that had little more than a slide, monkey bars and a seesaw. Back then, everyone would gravitate to the park, where Butler would always find large crowds, girls, and plenty of gang and criminal activity. Police eventually shut down the scene by buying one of the houses abutting the park, tearing it down and building a new one filled with surveillance cameras.

When Butler's mother, Mattie Paden, would find him at the park, she would often resort to waving a bat at him to make him go home. But she worked two jobs, sometimes 80 hours a week, to support the single-parent home and was limited to chasing after him in the family's Mercury station wagon when she returned from work. It wasn't enough. Butler and six friends -- Greg West, James Barker Jr., Robert Nellom, Andre King, Andre Love and Antonio Strong -- constantly were in trouble for vandalizing property and fighting. Butler estimates that he was in juvenile court 15 times before age 15.

The Gangster Disciples, who controlled the park, made a strong recruiting pitch, demonstrating how dealing drugs yielded quick money. Butler's uncles and a few cousins were already dealing, so he had no trouble getting started.

"We used to see the big dudes [drug dealers] come through, with their cars shining. We didn't have nothing," said West, who was known as Little Greg. "That's what drove us to it."

"We used to see the big dudes [drug dealers] come through, with their cars shining. We didn't have nothing," said West, who was known as Little Greg. "That's what drove us to it."

Butler made his first drug deal at age 11, pocketing $38. He would hide his gold watch and chains when he got home, and also had a newspaper route that served as a cover. Butler received newspapers at 3:30 each morning, delivered them and then hit the corner of 18th and Howe to sell crack before the sun rose.

"You can take a kid to school all day; he's in school for eight hours, he [doesn't] see the immediate impact," Butler said. "You can stay out [on the corner] for four, five hours and make $1,500."

During his freshman year at Racine Case High School, Butler gave his locker combination to a friend and allowed him to store drugs there. That same day, he noticed four police officers walking the halls. They entered Butler's classroom and arrested him. Along with the drugs, they discovered an unloaded .32-caliber pistol in the locker. Butler also was carrying $1,200 in cash.

Butler, West, Nellom, King and Strong were questioned by police. Had he been convicted of the gun charge alone, Butler would have served a lighter sentence, but he also claimed ownership of the drugs to protect one of his friends. West says now the drugs did not belong to Butler. "He took the case," West said.

Butler's family tried to persuade him to divulge who had put the drugs in his locker so he could avoid jail. "I couldn't see myself doing that," said Butler, who still refuses to provide the name. "I wasn't going to tell on anybody that I was rolling with, so I had to man up.

"I was hustling. I was doing what I was doing, so when I got caught up like that, I had to bite the bullet. When you're out there selling poison, it's going to come back. That's karma, man."

He spent the first two months of an 18-month sentence at the Racine Correctional Institution, an adult facility, before being transferred to the Ethan Allen School for Boys in Wales, Wis., a razor-wire-enclosed campus for youngsters convicted of murder, burglary and selling drugs.

When Butler was relocated to Ethan Allen, his mother followed the prison bus in the family station wagon, weeping for the entire 57-mile ride north. "He was with me ever since birth," Paden said. "To have your child taken away from you, it was devastating. I almost went crazy."

Butler cried as he saw his mother trailing. The family already was reeling from the conviction of his uncle, Carlos Butler, who had been sentenced to 10 months in prison for a gun charge a few months before.

Within his first month at Ethan Allen, Butler got into an altercation with a rival gang member from back home. Punished with 15 days in solitary confinement, he was forced to spend 23 hours a day in a 10-by-12, yellow brick cell, with a steel bed and a two-inch-thick mattress. His food was slid in through a small opening and he was granted an hour outside to clean himself.

Butler decided that he'd never be in that position again. He read Bible verses his grandmother, Margaret Butler, had sent him. Butler said he was drawn mostly to 1 Corinthians 13:11, which reads, "When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things."

One small window, sandwiched between steel bars, lit his room. Butler could peer out and see a basketball court.

One small window, sandwiched between steel bars, lit his room. Butler could peer out and see a basketball court.

"God puts stuff in front of you for a reason," he said. "That was my ticket out."

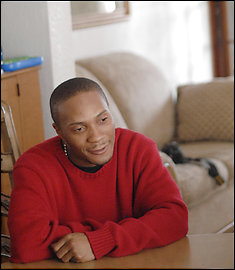

On the day he was released from Ethan Allen in August 1996, Butler, then 16, promised his mother that he'd never do anything to hurt her again. He also sought out his daughter, Camary, born less than a month after he was incarcerated. For Butler, who barely knows his father, it was another way to make amends.

"One of the main things I wanted to do was be the best father I could be because I didn't have a father," he said. "I know that void hurt me."

Butler's mother moved the family away from trouble, to a new home in midtown on Bluff Avenue. Eight days after Butler arrived there, he was getting a haircut on his porch when Andre King visited and asked him if he wanted to hang out at Hamilton Park. Butler, shackled by an ankle-monitoring device assigned to him after his release, told King that he couldn't leave the porch. Two hours later, Butler said, King was shot and killed.

Butler's mother moved the family away from trouble, to a new home in midtown on Bluff Avenue. Eight days after Butler arrived there, he was getting a haircut on his porch when Andre King visited and asked him if he wanted to hang out at Hamilton Park. Butler, shackled by an ankle-monitoring device assigned to him after his release, told King that he couldn't leave the porch. Two hours later, Butler said, King was shot and killed.

"If I wasn't on the bracelet, I would've been right there with him," Butler said. "That stuff, it takes a fire out of you, makes you say, 'This is not for me no more.' " Less than two years later, James Barker Jr. also was murdered at Hamilton Park, shot twice in the chest. Butler remembers rushing from his home to find a bloodied Barker removing his jewelry and handing it to his weeping sister before being moved to an ambulance.

A job at Burger King was one of Butler's first steps toward a different life. His friends routinely heckled him for mopping floors and removing french fries from the piping hot grease. "They'd see me with heat bumps, laughing at me," said Butler, who now owns several Burger King franchises. "I said, 'I ain't got to watch my back out here.' I set the example."

A Critical Decision

Richard Geller, 47, has been a member of the Racine Police Department for 24 years and last year he was honored with the department's award of excellence. The son of a Marine, Geller has spent practically all of his life in Racine. He considered attending law school at Western State University in California but instead chose a career in local law enforcement so that he "could give back to my community." Geller worked in the department's drug investigations unit during the mid-1990s, the most dangerous era in Racine's history, when it often had the highest per capita homicide rate in the state. "It was a time in the city's history that we're not sad to see in our rearview mirror," Racine deputy chief of police Art Howell said.

About 5 feet 10, slightly built, balding and with a salt-and-pepper mustache, Geller is far from a physically imposing man. But on that afternoon in January 1998, he had the power to play God with Butler's life.

Geller, by then the head of the department's investigations unit, had received a tip that there was drug activity in the garage of the home Butler shared with his mother and younger brother, Melvin Claybrook. He secured the search warrant and organized the raid. "To be honest, I had no idea who we'd find in the house," Geller said recently.

The identity of the person who put the crack cocaine in the garage is unclear, but Butler is adamant that it wasn't him. Geller knew of Butler's criminal past but was unaware that he was a promising athlete. He confronted Butler after finding the drugs, and Butler denied knowing anything about them. With his burgeoning basketball career possibly in jeopardy, he told Geller, "I don't need this now."

![Policeman Richard Geller watches a Wizards game with wife, Heidi, and son, Sawyer. Geller could have arrested Butler in '98, but chose not to. "[God] said 'I'm going to touch you so that you can touch others.' " Butler recalled. Policeman Richard Geller watches a Wizards game with wife, Heidi, and son, Sawyer. Geller could have arrested Butler in '98, but chose not to. "[God] said 'I'm going to touch you so that you can touch others.' " Butler recalled.](/sites/default/files/escape7.jpg)

Since Butler was the only person at home during the raid, Geller could have arrested him by citing "constructive possession," which makes the person in a home liable for what is inside. If convicted, Butler could have received at least 10 years in prison, maybe more given his prior record, Geller said. "It would've been bad for me, period," Butler said.

Butler's mother arrived while the officers were deliberating what to do with him, shocked to find police in her home after a trip to get flu medicine and soup for her son. Geller recalls her pulling him aside and begging him: "I promise you, if you give Caron a chance on this, you will never look back. You will never have to worry about him."

A very pragmatic man, Geller said he prides himself on a meticulous approach to his job. He believes police work is much easier when you treat people correctly. "I'm not saying that Caron might not have been involved in something at that point, but in my gut, I was pretty confident the dope wasn't his. I had done my homework."

Geller's supervisor told him that he had enough for an arrest, but left the final decision up to Geller.

"If this had been a situation where I knew going in that Caron was the guy selling the dope -- that he was the responsible party -- I'm not going to lie to you, he would've been escorted out of that house," Geller said.

He decided to let Butler go.

"I thought it was the right thing to do -- to see him go on the right path," Geller said.

But Geller and his supervisor left Butler with a warning. "They told me, 'If you get in trouble again, anything to do with narcotics again, you're taking this case, too,' " Butler recalled. "I was like, 'You don't have to worry about that.' "

Discovering the Game

Butler had always dabbled in basketball, but he developed a hunger for the sport during his months at Ethan Allen, where he played pickup games to win Little Debbie snack cakes and frosted doughnuts. And he soon became a standout at Washington Park High School.

Jameel Ghuari, director of the George Bray Community Center, persuaded Butler to play for his Amateur Athletic Union team. Ghuari, a community activist, coached Butler for three summers and later served as his mentor. He spent countless hours trying to convince Butler that basketball could be his means to a better life. It was a hard sell, Ghuari said. "He was still very influenced by his environment and those individuals who he hung around with," he said. "His mentality was still in the street."

His close friends noticed a change in Butler, though, after he attended the Spiece Run 'N Slam AAU Tournament at Purdue University in 1998. He led Bray Center to the tournament title and won MVP honors, besting teams featuring future NBA players Darius Miles, Corey Maggette, Quentin Richardson and Dwyane Wade. "He was a totally different dude," West said. "He said, 'I got something to prove.' He wasn't the same person."

Butler realized, finally, that he needed to leave Racine.

He asked a local drug dealer, James "J-Fee" Harris, for nearly $5,000 to pay the tuition at Maine Central Institute, a prep school Ghuari recommended to Butler when his eligibility with the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association expired before his senior season. "He said, 'Get off these streets,' and gave it to me," Butler said of Harris. "No strings attached."

He asked a local drug dealer, James "J-Fee" Harris, for nearly $5,000 to pay the tuition at Maine Central Institute, a prep school Ghuari recommended to Butler when his eligibility with the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association expired before his senior season. "He said, 'Get off these streets,' and gave it to me," Butler said of Harris. "No strings attached."

Harris is now imprisoned in Indiana.

Butler spent two years at MCI in tiny Pittsfield, Maine, to repair the academic transcripts damaged by his incarceration and to polish his skills on the court.

Connecticut Coach Jim Calhoun was familiar with Butler's past but never had any concerns while recruiting him. Coming from South Boston, Calhoun said, he could "sympathize with the streets a bit. With Caron, all you had to do was meet him. He was one of the best people I've ever coached."

After leading Connecticut to the round of eight in the NCAA tournament and scoring 32 points in a loss against eventual champion Maryland, Butler declared for the NBA draft following his sophomore season. The Miami Heat selected him 10th in 2002. He was traded twice in his first three seasons -- to the Los Angeles Lakers and the Wizards -- and says Washington has become a second home for him.

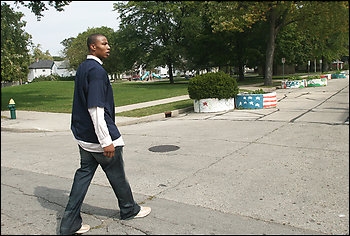

He lives in Centreville with his wife of more than two years, Andrea, and their 3-year-old daughter, Mia. His two other children, Camary, 12, and son, Caron Jr., 7, live in Racine. Butler provides financial support and visits them when he goes home in the offseason. He bought his mother a home on Lake Michigan in the northeast section of Racine, the city Butler refuses to abandon.

In the absence of the injured Gilbert Arenas, Butler has taken a greater leadership role and is having his best season as a pro, despite an injury that will keep him from playing in today's game. Butler still keeps memories of his friends close to him, though. After scoring 29 points in a win against Toronto on Dec. 1, Butler walked out of the locker room, slipped a newspaper out of his suit and smiled.

"Guilty," Butler said as he rolled up the paper and gripped it tightly. The day before, a jury had found Davion Davis of Racine guilty of shooting and killing another one of Butler's friends, Robert Nellom, in May 2006 at the Two Six Two Lounge, just a few blocks from Hamilton Park.

Last August, a fourth member of Butler's original group of friends, Antonio Strong, also was shot and killed.

"You see all that and you see people before they die, it's a question you ask yourself, like 'Why did God spare me like this, when I was out doing the same thing?' I can't stand going home and having to bury one of my friends. This gotta stop," he said.

"I just try to live life, live it the right way, live every day like it's your last. Seeing all the crazy stuff in the world, you've got to truly, truly take advantage of the time you're given here."

In September, Butler gave away about 700 coats to children at Gilmore Middle School in Racine after doing the same thing at a different school a year earlier. He also has given away bicycles and held a basketball camp. Such efforts led Racine Mayor Gary Becker to proclaim June 8 "Caron Butler Day." Emotional during much of the ceremony, Butler finally broke down, openly weeping upon receiving a plaque from Becker.

After the coat giveaway, Butler walked through his old neighborhood. Drivers passing by honked or shouted, "CB!" Butler waved and shouted back.

"I was [doing] some wild stuff out here," Butler said, pausing on the corner of 18th and Howe. "I walk this corner so proudly because I came from this block. I skipped school to be out here. My history is right here. Some things have changed [for me] from a growth standpoint and a money standpoint, but I'm still humble.

"I'm going to do whatever I can in my ability to not mess this up. . . . You try your best to do positives, do the right thing, influence kids not to go down the path you went down. When are people going to learn? You don't always have to be the same as you once was. That's why they call it mature. People change. People grow up."

In the years following his decision to set Butler free, Geller's colleagues often expressed their disapproval, believing Butler would never reform. The shouts that he would regret his decision eventually quieted to whispers, Geller said.

Geller runs into Butler's mother every so often in Racine and the two are on good terms. Geller and Caron have not spoken since that day. A few years ago Geller's wife, Heidi, bought him an autographed picture of Butler and it now sits on his desk. He often attends Milwaukee Bucks games and last month when they played the Wizards, he and Heidi were in the stands with their son, Sawyer, 10. Sawyer is only allowed to wear two NBA jerseys, the one worn by Bucks star Michael Redd and the one worn by the player his father could have arrested a decade earlier.

"The good that has come out of it has benefited this community a whole lot more than Caron's arrest would have," Geller said. "There is the thought, once a thug, always a thug. That isn't true. I've come to learn that."