- Contact

- Book

- 3D Foundation

- Butler Elite

- Staff

- 2018 17U

- - 2018 17U Photos

- - 2018 17U Videos

- 2019 16U

- - 2019 16U Photos

- - 2019 16U Videos

- 2020 15U

- - 2020 15U Photos

- - 2020 15U Videos

- 2021 14U

- - 2021 14U Photos

- - 2021 14U Videos

- 2022 13U

- - 2022 13U PHOTOS

- - 2022 13U VIDEOS

- 2023 12U

- - 2023 12U PHOTOS

- - 2023 12U VIDEOS

- 2024 11U

- - 2024 11U Photos

- - 2024 11U Videos

- 2025 10U

- - 2025 10U Photos

- - 2025 10U Videos

- Information

- Media

- Bio

"Solitary" by Caron butler

Spending time alone can be both therapeutic and traumatic. But it all depends on context.

For example, going for a drive at the end of a long day can be a great way to clear your head. Spending time in solitary confinement as a teenager? Not so much.

However, for me, the latter likely ended up saving my life. Fighting with a fellow inmate, who was also a member of a rival gang in my neighborhood in Racine, Wisconsin, led to me spending 23 hours a day, for two weeks, in a 10-by-12-foot cell.

My life up until that point seemed destined for failure. All the male role models in my family went through the penal system, incarcerated for drugs, guns or gang-related charges. They were all locked up at some point during my early years. I often wondered if everyone from my inner-circle would be killed in the streets or die in prison.

Fear, and the belief that I couldn’t change my ill-fated destiny, led me down the same path. By the time I was 11 years old, I was already selling cocaine on the south side of Racine. I had been arrested over a dozen times by the time I went to high school, but things came to a head when I was 15. I came to Racine Park high school with a .32-caliber pistol and let an older friend of mine use my locker to stash cocaine. Members of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives found both the gun and cocaine in my locker. As I said, the gun was mine but the cocaine was not. However, the code of the streets led me to keep quiet and accept that charge as well.

I was taken to Racine Correctional Institution — an adult facility — where I served two months of my 18-month sentence before being transferred to the Ethan Allen School for Boys. Don’t let the name fool you; this “school” was home to criminals who had committed robbery, rape and murder.

At just 15, I was a convict, facing more than a year behind bars, and I was a father-to-be. At an age where most teenagers’ biggest dilemma is who to ask to the next school dance, I was facing extreme life-altering situations.

Throughout all of this, my mother, Mattie Paden, was there for me. When I was arrested, she followed the police car in her blue Mercury station wagon. She even spent that night in her car in the parking lot because she didn’t want me to feel alone.

My mother worked two jobs and sacrificed so much for us to get by. Back then she wasn’t able to reap the benefits of her hard work. Coming home to eviction notices and violence in the neighborhood were not rare occurrences. Sometimes things seemed like they would never get better for us, but my mom always believed that we could make it through anything. More importantly, she believed in me. Even after I was sent away to Ethan Allen and she was still working two jobs, she’d make that long drive to see me for visiting hours, then she’d drive home with barely enough time for a nap before going to work again. My mother is the strongest woman I know. Without her love and support, I am not sure where I would be today.

During the two weeks that I was in solitary confinement, I reflected on the sacrifices my mother made and knew that I had to become a better man. I wanted to make her proud. I wanted her to be able to say, “That’s my son,” with a smile on her face rather than tears streaming down her cheeks. I spent many hours alone, writing her letters about my desire to make necessary changes in my life.

Some people might argue that jail turns people into better criminals. You can learn schemes and tricks on how to beat the system from fellow inmates. However, my experience was different. Being away from my family and losing my freedom influenced me to be a better human being. Without that time of desperation, I never really could’ve made the change that would save my life. It led to me becoming closer with God.

Sitting in that yellow brick cell, I would think about the cycle — how people get out of prison, only to return again. I knew relatives and friends that had spent their whole lives in that cycle. I didn’t want to fall into that. I wanted to get out and stay out.

Sitting in that yellow brick cell, I would think about the cycle — how people get out of prison, only to return again. I didn’t want to fall into that. I wanted to get out and stay out.

They say if you continue to do the same thing over and over, expecting a different result, it’s a sign of insanity. I didn’t want that.

While I was coming to this moment of clarity and making mental strides to begin going down the right path, my mom was once again doing everything she could to help me make that change. She moved from the chaotic south side of Racine to a more stable neighborhood in midtown.

This was crucial to my transition because, after serving nine months, I didn’t go back to the same community that I was in before. I was no longer surrounded by the criminal lifestyle. I began taking action to become a better man. I connected with my daughter, Camary, who was born just one month after I was incarcerated. I also immediately got a job at Burger King.

Needless to say, it was a big change going from selling drugs to flipping Whoppers. The day I was arrested at school, I had $1,200 cash on me. Suddenly I was making minimum wage and wouldn’t come close to seeing that kind of money after a month’s worth of mopping floors and working the grill.

It took time to adjust to this new lifestyle. I saw guys rolling around in new cars, having new clothes, new Jordans — reminders of all the things I couldn’t afford. Old “friends” would come in and make fun of me because of my uniform. But I knew I couldn’t go back to jail — no matter how tempting the lure of quick money was. At Bray Community Center in Racine, where I first started playing organized basketball, there’s a photo of 21 black men, many of whom I used to run with. All were under the age of 25, and now they are all dead. I knew I had to turn my life around.

At Bray Community Center in Racine, where I first started playing organized basketball, there’s a photo of 21 black men, many of whom I used to run with. All were under the age of 25, and now they are all dead.

After being released from Ethan Allen School for Boys, I enrolled at Park High School. Though I excelled on the court, I would make another decision that would greatly benefit my future. My family and members of my community rallied behind me to help me get into a prep school. I would transfer to Maine Central Institute, a prep school in Pittsfield, Maine. That was a big turning point in my life. Because of my on-court performance there, I developed a relationship with UConn coach Jim Calhoun.

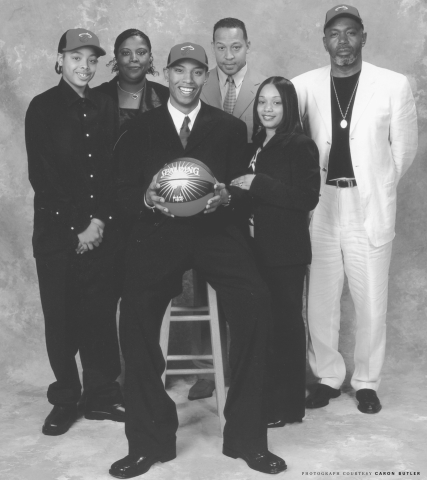

Receiving a scholarship to play at UConn was truly a life-defining experience. No one in my family had ever gone away to a four-year university. Everyone in my family felt like the bar had been raised. A life of crime was no longer the answer.

It’s been 20 years since I spent two weeks alone in that 10-by-12-foot cell, but I remember it like it was yesterday. My mother and I reflect on our times of adversity all the time. To recognize the delta between where we are now and where we once were — it’s surreal and it’s a blessing.

Now I speak about my journey to younger generations who are at-risk because I was them. I didn’t have an easy, structured upbringing and then suddenly became an NBA All-Star and champion. I’ve spent time in jail. I lived in a neighborhood infested with drugs and gang culture. I grew up seeing people get stabbed and shot. Despite all of that, by the grace of God, hard work and the devotion of my mother, I’m in the position that I’m in today. Younger generations need to see a real, tangible example of making it.

Maybe I went through all of this to serve them.

Read more at http://www.theplayerstribune.com/caron-butler-my-brothers-keeper/