- Contact

- Book

- 3D Foundation

- Butler Elite

- Staff

- 2018 17U

- - 2018 17U Photos

- - 2018 17U Videos

- 2019 16U

- - 2019 16U Photos

- - 2019 16U Videos

- 2020 15U

- - 2020 15U Photos

- - 2020 15U Videos

- 2021 14U

- - 2021 14U Photos

- - 2021 14U Videos

- 2022 13U

- - 2022 13U PHOTOS

- - 2022 13U VIDEOS

- 2023 12U

- - 2023 12U PHOTOS

- - 2023 12U VIDEOS

- 2024 11U

- - 2024 11U Photos

- - 2024 11U Videos

- 2025 10U

- - 2025 10U Photos

- - 2025 10U Videos

- Information

- Media

- Bio

WASHINGTON POST: Butler takes readers inside a life filled with guns, guts and grit

Caron Butler’s biography is filled with guns.

There was the .32 revolver he bought for $100 as a 12-year old — not long after he started selling narcotics out of his little red wagon — and the guns he and his teenage friends would fire into Lake Michigan, shooting toward boulders and jet skiers and anything else. There were the guns used in drive-by shootings in Butler’s native Racine, Wis., and the guns toted by rival gang members wearing Jason masks during a shootout in the park.

There were the guns ATF agents pulled on Butler in a classroom during his freshman year of high school, and the gun they soon found in his locker, part of the sting that wound up sending the future NBA star to jail. There was the gun he shot himself with at a high-school dance — a story he never even told his mother, but that’s included in his upcoming book, “Tuff Juice: My Journey From the Streets to the NBA,” which will be released Oct. 7.

And, of course, there were the guns that Gilbert Arenas and Javaris Crittenton brought into a Verizon Center locker room in 2009, an incident that transformed the Wizards organization and interrupted the course of Butler’s career.

It’s bracing to read about the violence surrounding a pre-teen whose life almost got buried during the crack epidemic of the 1990s. It’s just as unsettling to read a detailed recounting of the Arenas-Crittenton showdown by one of the few people who witnessed it firsthand.

Butler describes the card game disagreement that started on the team’s charter flight, when teammate Antawn Jamison “leaped up, shoved Javaris’s shoulder down on the table, and held it there with the full weight of his body while telling him to calm down.” He writes of the airport shuttle ride later that night, when the fighting continued and GM Ernie Grunfeld pleaded for Butler to “talk to them.”

He quotes Arenas telling Crittenton, “I play with guns,” and the young guard responding, “Well I play with guns, too.” And he provides a harrowing play-by-play of the next day’s events, when Crittenton “pulled out his own gun, already loaded, cocked it, and pointed it at Gilbert.”

Other players fled. Someone called 911. And Butler — who was at once taken back to the south side of Racine — talked calmly to Crittenton, telling him what was at stake. Why go through such intense details now, with Arenas out of the league, Crittenton in prison and Butler about to play for his seventh team in seven years?

“It was a huge part of my career, something that altered my career; it was a decision made by two young men that kind of led to how my career was shaped,” Butler said Tuesday afternoon. “We just knew that whatever we had going, whatever it was, it was over, because of that situation.”

Butler had for years been thinking of turning his story into a book; Jay Leno suggested it to him as early as 2005, although he thought the idea seemed “corny” at first. Still, around that time, his agent arranged for him to record interviews about his early years: being raised by a single mom who worked 80-hour weeks, riding a Big Wheel so battered that no wheel remained, seeing his mom’s boyfriend shooting heroin in their apartment, hanging out with friends smoking joints rolled in pages of the Bible, dealing crack at an age when many boys have yet to hit puberty, his lingering foot issues from wearing too-small shoes behind bars.

He recorded interviews about his time in a juvenile facility, his transition into serious basketball, his attempts to leave the streets behind, and his various friends and family members who struggled against the same forces, many of whom wound up behind bars, or dead. By last year, Butler felt ready to put this on paper. A co-author interviewed many of his family members and childhood friends; the rawness of their stories surprised even Butler.

“I was like damn, you told him that?” the 35-year old said he thought when he listened to the interviews. “When we put it all in chapters and I read it from one ’til the end, I was like ‘Damn!’ Every situation, I was like, ‘Damn!’ I just kept saying it.”

It seems like a movie script, and not for nothing. Butler still cites with approval the headline of a Post story about his life: The Great Escape. One of the new book’s cover blurbs is written by Mark Wahlberg, and there have been talks about turning the story into a film.

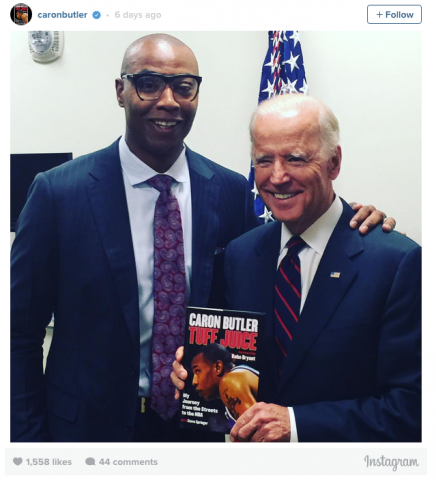

Butler even visited the White House this week with Lt. Rick Geller, the Racine cop whose decision not to charge Butler after finding drugs in his home allowed Butler’s life to change course. They appeared with Vice President Joe Biden and Attorney General Loretta Lynch at an event about improving communication between youth and law enforcement; Butler, not surprisingly, wound up chatting up the vice president.

Butler, who played longer in Washington than anywhere else, said the D.C. area still feels like home. Eddie Jordan, who gave him the “Tuff Juice” nickname, is still the only coach who became a close friend, and Butler said to this day he feels “horrible” about the unrealized potential of those Wizards teams. His book does not focus on regret, but it’s unavoidable when discussing that era.

“Looking back, we really [messed] up a good thing,” Butler writes. “Add maturity, a more serious attitude, and a firm commitment to work together and who knows how far we could have gone. Instead, it was just one blown opportunity after another.”

That, though, is the rare missed opportunity in Butler’s adult life. He’s gotten business advice from Mark Cuban, studied player contracts with Stan Van Gundy and explored media opportunities in recent years, part of his post-basketball planning. He also has made enough money that he could retire to the country, “just ride on a tractor and plant stuff, be with my peapods,” he joked.

Whatever comes next, Butler said he plans to keep re-telling his story, to new generations and people who’ve heard it before, to radio hosts and television audiences and to anyone else who will listen. Why?

“You’re living this unbelievable life, and you’re on this magic carpet ride of a career, but they need to know that you went through that,” he said. “Because if you come from this walk of life, they can respect your stories so much more … It’s just a certain feeling that you get: damn, every time this guy jumped off the porch, he saw what I saw, went through what I went through. I know he knows exactly how I feel in this moment. And he made it.”

Read article by Dan Steinberg of the Washington Post here.